Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin is a Nobel Prize-winning scientist whose research advanced the field of X-ray crystallography and determined the structures of several important biochemical substances, including penicillin, vitamin B12, and insulin.

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin: Developing a Lifelong Passion for Chemistry

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin was born in Cairo, Egypt on May 12th, 1910 to a family with a collective passion for archeology. Both of her parents were archaeologists, and Hodgkin may have followed this path herself, if not for a childhood fascination with chemistry and crystals. Her mother supported her interest in science as it continued to grow during Hodgkin’s formative years.

Although Hodgkin spent many youthful days in the Middle East and North Africa with her parents, most of her formal schooling took place in England. Between 1921 and 1928, she attended Sir John Leman Grammar School in Beccles. It was during her time at this school that Hodgkin received a book about using X-rays to analyze crystals, a topic that was to become her life’s work. Her interest in science increased further when Hodgkin and another female student were allowed to study chemistry with their male classmates, an opportunity that helped Hodgkin decide to continue her studies in science at a university.

Somerville College, Oxford. Image by Brigade Piron — Own work. Licensed underCC BY-SA 3.0, viaWikimedia Commons.

During part of her first year at Somerville College in Oxford, Hodgkin studied chemistry and archeology, showing her continued interest in her parents’ work. But after attending a course in crystallography and receiving advice from her tutor, she chose to focus onX-ray crystallography, a process that determines the 3D structures of crystals through light diffraction. This emerging technology was full of new challenges and opportunities, and Hodgkin was ready to tackle them.

In 1932, she graduated with first class honors and moved to Cambridge University to continue her studies. There, she worked with John Desmond Bernal, a pioneer in X-ray crystallography. They worked together to determine the 3D structures of multiple complex organic molecules, causing Hodgkin to realize the great potential of this technique.

Later, she was given a fellowship back at Somerville College, which she held until she retired in 1977. In this position, she taught many students, including future Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Much of her fame stems from a few important discoveries that she made during this fellowship. We’ll discuss these achievements in the next section.

Fostering Advancement in X-Ray Crystallography Research

X-ray crystallography involves striking a crystal with an X-ray, causing a beam of light to diffract. From this, researchers generate diffraction patterns, which they can use to discover the crystal’s structure. Using this technique, Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin made many important discoveries in the field of chemistry throughout her lifetime.

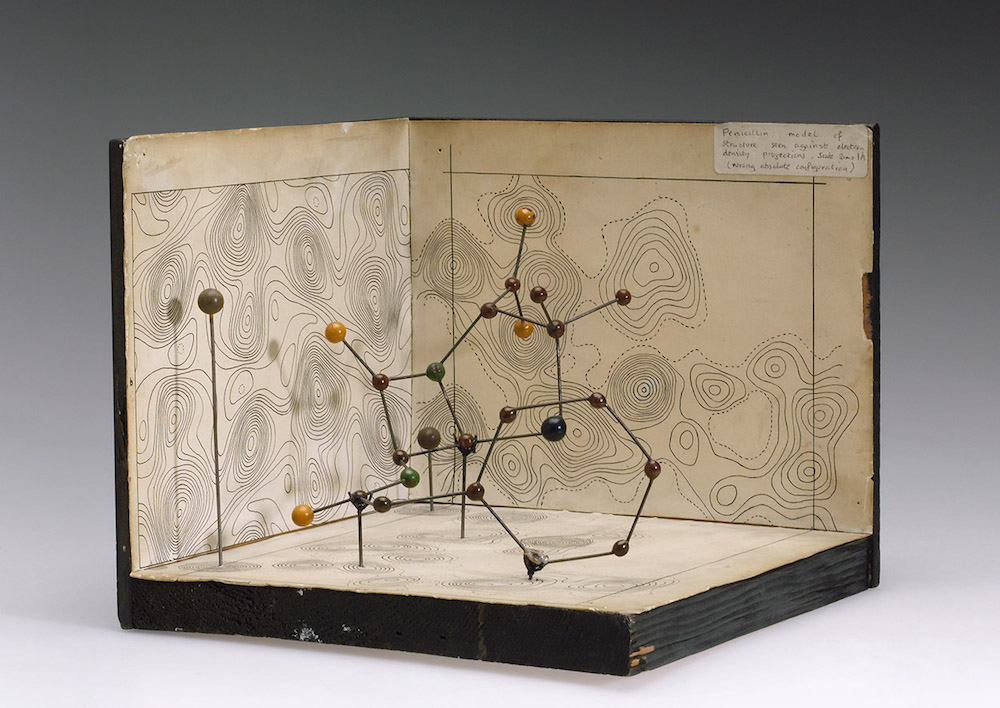

In the 1940s, Hodgkin and her colleagues made their first major breakthrough when they discovered the structure of penicillin. To make this discovery, Hodgkin utilized X-ray diffraction images as well as detailed calculations and analyses. This breakthrough helped manufacturers produce chemically modified penicillin that is still in use today.

Hodgkin’s penicillin structure. Image from the Science Museum London and the Science and Society Picture Library. Licensed underCC BY-SA 2.0, viaWikimedia Commons.

Hodgkin then turned her research efforts toward investigating vitamin B12. Through careful studies, she learned that its structure could be determined by X-ray crystallography, and using this technique, she managed to confirm the structure of vitamin B12in the mid-1950s. Due to these discoveries, she was awarded a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1964 — making her the third woman to ever receive this honor.

One of Hodgkin’s long-term projects was deciphering the structure of insulin. She had received a sample of crystalline insulin earlier in her career, and although intrigued by this substance, it was too complex for the X-ray crystallography techniques of the time. This didn’t stop Hodgkin, however. She and her colleagues continuously improved X-ray crystallography techniques, and after more than 30 years of hard work, Hodgkin and her team resolved the structure of insulin in 1969. This research has benefited diabetics by enabling genetic engineers to alter the chemistry of insulin.

Shaping Modern Uses of X-Ray Crystallography

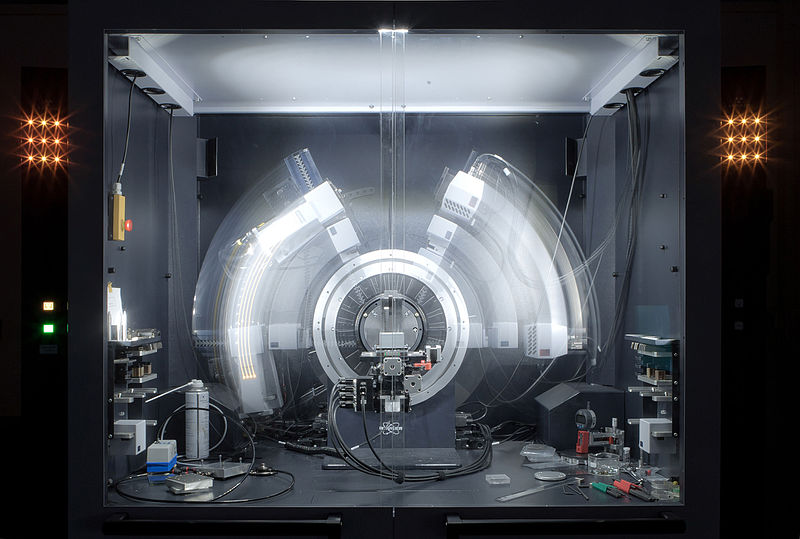

Today, Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin’s beloved field of X-ray crystallography continues to grow and is frequently used for medical-related studies. For instance, scientists at the Scripps Research Institute used X-ray crystallography tosolve the structure of biological machinery for the lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV). This common virus may be a missing link between two classes of viruses. Learning its structure can help us better understand its close relative, the lethal Lassa virus.

A modern machine used for X-ray crystallography. Image by Kaspar Kallip — Own work. Licensed underCC BY-SA 4.0, viaWikimedia Commons.

Research studies involving X-ray crystallography may also provide a better understanding of diseases like Alzheimer’s, schizophrenia, and Parkinson’s. By using this technique, a research team from the Technical University of Denmark (DTU) and the University of Oxforddiscovered the molecular structure of dopamine betahydroxylase (DBH). This enzyme controls the conversion between two major neurotransmitters: dopamine and norepinephrine. All three of these elements are involved in the disorders mentioned above. Hopefully, this research will aid in the development of pharmaceutical treatment methods for these diseases.

It’s crystal clear that the legacy of Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin continues to live on in science. Today, let’s wish her a happy birthday!

Further Reading

- Find out more about the life ofDorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin

- Want to learn about other scientists whose work has changed the world? Browse theseblog posts

- Read about using simulation to advance medical treatment on the COMSOL Blog:

Comments (0)